A compelling exploration of a different world

I read Nyssa Glass and the House of Mirrors, by H.L. Burke, on the recommendation of a friend and am very glad to have done so: I really enjoyed this story.

The plot follows a young lady - Nyssa, of course - through a series of exploits as she tries to extricate herself from being unjustly accused of murder. Her background is dubious enough to make the accusation likely to be believed, but she is determined to deserve the trust of her employer Mr Calloway, and her former teachers at Miss Pratchett's School for Mechanically Minded Maids. This determination keeps her going through puzzles, dangers, and difficulties.

On the surface, her basic task seems clear - find a way into a seemingly abandoned house and retrieve a missing item. But inevitably things are not so simple. The house turns out to be well-defended, although the protective systems are overdue for servicing and overhaul, and it is not so empty as it seems at first sight...

The action takes place almost entirely within a single day - barring some necessary flashbacks and a brief "what followed" section - but it is easy to forget the shortness of the timespan as you are carried along with the action. You reach the end of the book feeling that you have come to learn a great deal about her, owing to the intensity of her experiences.

A recurring theme of the book is the question of who Nyssa can rely on. Sometimes she makes the wrong decision, and finds herself having to work out how to undo the difficulties resulting from this. Her life experiences have not disposed her to be particularly trusting, and suspicion of motives easily rises to the surface of her thoughts. But the ongoing need to work out who is dependable and who is fickle is a major thread of the book, and one which several of the characters grapple with. The answers to these questions shift multiple times through the book as various facts and snippets of background become clear.

The author's chosen style is most like Steampunk, though with her own personal spin on the conventions of that genre which worked well for me. The level of scientific and technological accomplishment was a perfect complement to Nyssa's skills and abilities. Both feel entirely credible and I was fully immersed in the tale. I particularly liked the approach towards mechanical intelligence was handled - a very different route to our society's, but it is a persuasive and compelling alternative. There is a point where curious enquiry of possibilities gives way to the horrified realisation of reality, and this is handled particularly well.

House of Mirrors is a YA novel and the personal interactions reflect this. However, this should not deter anyone, and there is ample interest and character depth to satisfy an adult reader. The cast of characters is comparatively small, and the end of the book strongly suggests that other books set in this world will follow in the future. I certainly hope so, and will be looking out for them.

(This review was originally prepared for The Review blog, http://thereview2014.blogspot.co.uk/)

Phobos and Deimos - history and speculation

Today’s blog bridges past and future, and focuses on Phobos andDeimos – the two moons of the planet Mars, named after the two chariot horses of the Greek god of war (Ares, for whom Mars is the Roman equivalent).

These moons were discovered by the American astronomer Asaph Hall at the Naval Observatory at Washington DC in 1877. He had been searching for them for some time, and was at the point of giving up when his wife Angelina encouraged him to persist. The following night, in a serendipitous moment even better than fiction, he was able to identify Deimos, and six days later he spotted Phobos as well.

Map of Laputa and Balnibarbi (Wiki)

Map of Laputa and Balnibarbi (Wiki)

But this tale goes back about 150 years before that, to 1726 and the satirist Jonathan Swift. In the third part ofGulliver’s Travels, having visited the better known lands of the miniature and gigantic – Lilliput and Brobdingnag – Gulliver arrives at a realm of scientists, called Laputa, floating in mid-air. The inhabitants are brilliant, but also implacably ignorant of worldly matters, and as a result, their ideas are usually impractical. Theirs is an interesting story, but the key paragraph from today’s perspective is in the third chapter, and reads as follows:

They have likewise discovered two lesser stars, or satellites, which revolve about Mars; whereof the innermost is distant from the centre of the primary planet exactly three of his diameters, and the outermost, five; the former revolves in the space of ten hours, and the latter in twenty-one and a half

The corresponding figures agreed by astronomers today are 1.38 and 3.46 diameters rather than 3 and 5, and 7.7 and 30.3 hours rather than 10 and 21.5. So his values are remarkably close to those agreed today, yet he had no apparent way to know them. This curiosity has excited a lot of energetic speculation, and no little conspiracy-minded thinking.

Relative sizes of Phobos (left) and Deimos (right) as seen from the Martian surface (NASA/JPL)

Relative sizes of Phobos (left) and Deimos (right) as seen from the Martian surface (NASA/JPL)

It seems likely – taking a more sober view – that he was basing his ideas on patterns of numbers. Mercury and Venus have no moon, Earth has one, and at the time Jupiter was known to have four. Five moons had been spotted around Saturn, and it would be a reasonable guess that another three would be found to give a total of eight. What more natural suggestion than that Mars had two? Kepler had made a similar suggestion, back in 1610.

Swift’s figures for the orbital size seem to be copied from values for Jupiter’s innermost moons Io and Europa, and the orbital period is then derived on the assumption that Mars has the same mass as the Earth. So his speculations may in fact be perfectly logically deduced, given the limited information at his disposal.

But the oddity about these moons did not stop with Swift. Nearly 15 years before Asaph Hall, a team led by H L d’Arrest at Copenhagen, working under more ideal viewing conditions, had failed to detect them. Not only that, but both moons are extremely light for their size, and the orbit of Phobos is close enough to Mars that it will not survive long in planetary terms – it is steadily decaying towards the fringes of the atmosphere. Finally, the surface of both moons is unusually dark – they are among the least reflective bodies in the solar system.

“That’s no moon” (Wiki)

“That’s no moon” (Wiki)

So the idea spread in the late 1950s that they were not natural moons at all, but artificial satellites put into orbit by a hypothetical Martian civilisation sometime between d’Arrest and Hall. This particular idea persisted right through to the presence of our own spacecraft orbiting and landing on Mars. I dare say that some people still adhere to it – after all, you can quite easily believe that an advanced race might disguise an artificial satellite as a moon.

But there are genuine unknowns still about these moons. Nobody has yet come up with a totally convincing theory of their origin – did they cool from the original disc of solar system matter at the same time as Mars itself? Are they splinters from Mars resulting from a prior collision with a suitably large body? Or were they captured from the relatively nearby asteroid belt?

Their low density has also attracted interest. Are they only very loosely packed collections of rubble-like material, rather than solid rock? Or perhaps there are significant cave-like voids riddled through the volume?

Until such time as we establish some kind of real presence on Phobos and Deimos, thus starting the real history of those moons, some of these ideas will remain purely conjecture…

Phobos transit against the sun, from Opportunity rover (NASA/JPL)

Phobos transit against the sun, from Opportunity rover (NASA/JPL)

An interesting glimpse into a pre-Raphaelite world

The Crimson Bed, by Loretta Proctor, is a tale of romance and family life set around the fringes of the pre-Raphaelite artistic movement in England in the mid nineteenth century. As such, historical figures such as Rosetti, Ruskin and Millais hover in the background, while the book's focus is on those who circled around them, as artists, art lovers, dealers, or collectors. Art, whether painted or verbal, is central to the plot, along with the pretences that art thrives on, such as contemporary models of humble origin being portrayed as nobility, or tragic heroines.

But Loretta also probes those darker and vastly more damaging pretences which lurk within human relationships. Lies, deceit, and the natural urge to bury past indiscretions all threaten the lives and wellbeing of the characters. Each person has a facet of their past which they would prefer to hide, even knowing the corrosive effect that concealment has on friendship and love. These interlocking secrets increase in their destructive potential through the book, and the central question becomes whether particular relationships can or cannot survive the revelations, as they inevitably surface.

One of the aspects of the book I found most fascinating was its view of society at the time. For a few, the complex web of Victorian social expectations provided reassuring and proper boundaries to conduct. But for many others, it was an arbitrary and constricting prison. But how could it be challenged? For some, the retreat towards a romanticised past appealed. Others wanted to accelerate towards a different future. Still others wanted to directly subvert the status quo by means of acts that society deemed illegal or immoral. The world of artists in The Crimson Bed tried all of these, and more.

Technically, the Crimson Bed has been well prepared, with a mere handful of formatting slips. I found that the last few chapters, while crucial in completing some aspects of the plot, seemed a bit disjointed, and I wonder if the transition from continuous action to future consequence could have been smoother. However, this did not detract from my enjoyment of the book, and my appreciation of a world I knew little about.

How far away is Artificial Intelligence?

Over the next few days, Google’s Go-playing algorithm,AlphaGo, will take on the current world Go champion, Lee Se-dol. It is an event which is being watched closely by both Go players and coders, since until very recently Go was thought to be a game intractable for machines to play competently. (At the time of uploading to this blog, AlphaGo is 2-0 in the lead)

I’ve worked in various ways with AI over a lot of years now, so thought it was high time I wrote about it here.Far from the Spaceports, and the in-progress follow-up By Default, have human-AI relationships at their heart. Mitnash, a thoroughly human investigator and coder, has Slate as his partner. Slate is an AI – or persona, as I prefer to use in the books – and the two work together in their struggle against high-tech crime.

International Helicopter Safety Team (IHST) workshop presentation from HeliExpo 2013

International Helicopter Safety Team (IHST) workshop presentation from HeliExpo 2013

How far are we away from this? In my opinion, quite a long way. There have been huge advances in AI during my working life. This has largely been made possible by corresponding advances in the speed and capability of the hardware systems on which they run. However, creative ideas for how to code learning algorithms and pattern recognition have also come taken huge strides. Nevertheless, I don’t think we are very close to working with Slate or her fellow personas just yet.

Of course, you have to be mindful of a quote attributed to Bill Gates: “We always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten.” But that said, I still think we’re some way off.

Neural network design (Wiki)

Neural network design (Wiki)

There are a lot of different, and very useful, ideas as to what constitutes intelligence, but for the purpose of this blog I am largely focusing on the abilities to learn and then detect meaningful patterns, work usefully with inconsistent or poor quality information, and communicate about all this with another individual in such a way that both parties can revise their opinions.

Part of the problem is that most people are working on a very small part of the problem, and the organisation paying them only really wants quite a specific outcome. So one team might be working on machine health monitoring and fault prediction, to improve aviation safety. Another will concentrate on whatever is needed to identify objects in photographs. Another on voice recognition. Another on being able to beat human champions at a specific game. And so on. Comparatively few are integrating all this into a single entity.

Senet board from Tutankhamun’s tomb (Wiki)

Senet board from Tutankhamun’s tomb (Wiki)

Human intelligence is also noteworthy for being able to adapt flexibly to new situations, calling for similar but not identical responses. So my guess is that Lee Se-dol probably also plays an outstanding game of chess, or Senet, or any of dozens of board games. At a guess, he could probably hold his own very well at some game he had never seen before, after a comparatively brief explanation of the rules. I have serious doubts as to whether Google’s codebase could make such a transition.

Another issue is repetition and predictability. If you’re coding a safety system, you really want to know that the same set of circumstances will lead to the same consequences. Quite apart from giving confidence to your immediate users, there is the whole matter of getting the system qualified for use. Imagine your system has failed to recommend replacement of a critical component. There has been a crash, and you are at the investigation. “Why did your system fail to recommend that the component be changed?” And you reply, “Oh, I don’t know – it says something different every time.” I can’t imagine this going down very well with the investigation committee. For the reaction of a friend, however, unpredictability is part of the fun.

Betty the problem-solving crow (BBC)

Betty the problem-solving crow (BBC)

We find it difficult to define what intelligence really is, or which part of our being is responsible for it. Recent comparative studies in which bird and primate intelligence are contrasted, have questioned the idea that it is seated in the cortex: birds don’t have such a thing. In the light of such basic uncertainty, corporate reluctance is understandable. It is hugely easier – and hugely more cost effective – for an organisation to say “build me a system which can identify patterns of word use by different authors” than “build me intelligent partners for my human staff.”

As someone working in a tech industry, I am keenly aware of, and excited by, the possibility of AI. How would my team carry out quality assurance for such a system? It’s often hard enough to do this for a complex but entirely rule-bound application. The challenges are immense.

But as an author, I am entirely free to suppose that all that has been done, and focus on the storytelling issues of how such a relationship would work.

Another fine Dawlish book

This review is for Britannia's Spartan, by Antoine Vanner. It is available at Amazon, Goodreads, etc but doesn't seem to have made it to Booklikes' own listings just yet.

Britannia's Spartan is the fourth in Antoine Vanner's Dawlish series. I have been following these from the beginning and have very much enjoyed the introduction to the world of the Royal Navy of the late nineteenth century.

This was a period of vast technological and social change. At the start of Nicholas Dawlish's fictional life, naval battles were still fought between wooden sailing ships armed with muzzle-loading cannon, of a basic design unchanged since Tudor times. By the time of Britannia's Spartan - the 1880s - he is commanding a steel-hulled ship driven by steam power, with breech-loading guns mounted in sponsons, carrying and being vulnerable to torpedoes. Rudimentary submarines were under development. The only major game-changer in naval warfare which did not appear in the nineteenth century was the aircraft, and these would also make their appearance before Dawlish's death in 1918 (still many books away, I am happy to say).

So, somebody in Dawlish's position had to master an ever-changing series of demands, if he was to continue to progress in his career. Men like Dawlish had been inspired by the careers of Nelson, Pellew, and the like, but the practical business of running a ship had changed radically since their day.

At this time England was, at least nominally, at peace. Ship captains were expected to have the ability to represent both their nation and their monarch as surrogate diplomats, not simply as warriors. However, the reality of service in foreign waters, accompanied by a degree of isolation from superior officers which is hard for us to contemplate, meant that every encounter could potentially be hostile. Some countries held grudges against England, and some factions within a country might attempt a surprise attack to gain some political advantage. There was, quite simply, no way to be sure whether the ship seen coming over the horizon was friend or foe. Dawlish's career, and the lives of his crew, depend constantly on his making the right assessment.

Each Dawlish book so far has focused on a different theatre of action. Britannia's Spartan takes our hero to the Far East, where rivalries and alliances between Korea, China, Japan and Russia have to be understood, and then turned to British advantage. For Dawlish, these cultures are opaque and challenging, as well as stirring up difficult memories of the early years of his naval service. Is he able to identify friend and foe quickly enough to meet the challenges, both on the field of battle and in the political arena?

In earlier books, Dawlish's naval battles, when they are forced on him, have often been in confined spaces such as river valleys, or around coastlines. Here, on the other hand, we are able to witness him working in the open sea. Ship handling, rather than judicious use of the terrain, is the key to success. Dawlish's ship, Leonidas, is technologically ahead of many ships in this part of the world, but not necessarily all of them. The skills of captain and crew must make up for any shortfall.

But sometimes battle has to be declined, and Dawlish must weigh carefully the consequences of both action and inaction. One of the most poignant moments in the book - and perhaps the one best illustrating Dawlish's own development as a ship captain - is when he has to decide not to provide help to a Chinese landing party who have been ambushed. Never reinforce failure is a military maxim used by von Clausewitz, Napoleon and countless others, back into antiquity and forward to the present day - and Dawlish is forced to adhere to the maxim despite the human cost. In the end he is able to redress the balance, but the moment has clearly weighed very heavily on his soul.

Both militarily and politically, Britannia's Spartan is a very strong book. Challenges must be faced at sea, during marine landings, and in ornate houses and palaces of state. It is a different world than the Victorian England that Dawlish has left behind. My only regret is that we meet so little of Florence, Dawlish's wife, who is a splendid character in her own right. Given the geographical setting, this was inevitable, but I still missed her.

All in all, Britannia's Spartan comes strongly recommended by me, whether or not you have read the earlier books in the series. Each is self-contained, and you can start to know Dawlish and his career at any point.

This review was originally written for The Review (http://thereview2014.blogspot.co.uk/2016/02/richard-reviews-britannias-spartan-by.html)

Basic elements - food

(Original post at http://richardabbott.datascenesdev.com/blog/index.php/2016/02/03/basic-elements-food/)

Here's the next in the Basic Elements series - this time looking at food. Life needs food - human life just as much as any other kind of life. And for a great deal of humanity's existence, finding an adequate supply of food has dominated communal needs. Douglas Adams, with his usual flair for insight, wrote of the three phases of every major Galactic civilisation, characterised by the questions "how can we eat?", "why do we eat?", and finally, "where shall we have lunch?". Many readers will probably think of themselves in the third phase, but it's worth remembering that a huge number of people on Earth are still struggling at phase one.

After the glaciers of the last ice age retreated, about 12,000 years ago, hunter-gatherer groups followed the milder weather back north, resettling tracts of land which had been their distant ancestors' homes long before. They followed not just the warmth, but also the herds and flocks as they migrated, and the seasonal yield of trees and bushes. Small migrant groups could eat off the land tolerably well, so long as they were willing to keep on the move, and retained a good pragmatic understanding of seasonal changes. They were self-sufficient.

- The spread of farming through Europe - Eupedia

Then farming came along, spreading across Europe from south east to north west. Farming communities have to stay put, not just season to season but also year to year. Fixed territory, and its ongoing fertility, become crucial. Our remote ancestors must have seen a clear advantage in this way of life, partly no doubt because it could support much greater populations, but it also brought risk. A bad year can signal disaster - and it is no longer possible just to follow the herds elsewhere. Your communal wealth can no longer easily be moved, and a good parcel of land somewhere nearby has probably already been settled. Either you stay put, and try to wait out the famine, or you go to war.

- Agra Street Market

But another corollary of settled communities is that they typically have a surplus of some things - and a surplus can be traded for whatever you lack. So you hedge, accepting that you cannot grow or produce some goods, and relying on your neighbours who can. You grow less dependent on your immediate fields to give everything you need, but more dependent on the resources of a wider area.

The historical fiction I write is set in a place and time where the dependence on other places has not become too firmly fixed. Kephrath and her sister towns certainly make use of trade links, but for bulk supplies are largely self-sufficient. Four towns together, and their hinterland, can manage.

The process of increasing specialisation of any one place, and increasing dependence on an ever larger area, has continued largely uninterrupted ever since. In both World War 1 and 2, arguably the biggest threat to the United Kingdom was the U-boat blockade cutting the nation off from resource supplies. There were great efforts to boost the domestic food supply, but a modern nation at war needs a whole array of raw materials which come from many sources - coal, oil, iron ore, rubber, exotic trace minerals, and so on. Without convoys bringing these in, the most abundant supply of food would still have lost the war.

- Cover - Foundation

Looking into the future, different authors have predicted different outcomes. In his Foundation series, Asimov reckoned that the trend of reliance on ever bigger areas would continue unchecked. Trantor, the capital planet of his Galactic Empire, grew no food at all, and depended on the agricultural wealth of multiple nearby star systems - an Achilles heel which was to prove fatal. Star Trek, on the other hand, assumes a technological solution in which energy can be converted into food from information templates in a replicator. The only thing you now need is an energy source - such a world is effectively reverting all the way back to hunter-gatherers foraging for supplies as they travel.

- Guinea pigs - Wikipedia

The solar system of Far from the Spaceports is more like Asimov's model, though of course vastly smaller in scale. There are no food replicators or protein resequencers. None of the settlement domes has hinterlands of lush fields able to grow local crops. The best that can be done out in the Scilly Isles of the asteroid belt is hydroponic farming - small scale and energy hungry. Otherwise there's imported goods, whether carried in fresh or (more compactly) freeze-dried. Or - perhaps amusingly but, I think, credibly - there are very small scale livestock solutions.

![]()

“Now, Mister Mitnash, were you wanting the chicken or the fish tonight?”

I hesitated, not being very sure. She laughed.

“No point spending too long deciding. It’s all guinea-pig anyway. I just prepare them a mite differently and you’d never know they’re the same animal. And it’s what you’ve been having everywhere else on Scilly.”

“Truly?”

“To be sure. Tell me now, where did you eat when you arrived on St Mary’s?”

“Taji’s.”

“And what did you have? His Venusian azure duck wrap?”

I nodded, and she carried on, “So did you honestly think he pays to ship real duck all the way out from Earth? Just to cook it and put it in a wrap? No, Mister Mitnash, all his menu is actually guinea-pig, but he’s very good at disguising it. For just me here, I only need one male and half a dozen females. Taji has three males and thirty females. Or something like that. So now, would you like the chicken or the fish?”

I thought about it and wondered if it would make much difference.

“I should like the chicken tonight, Mrs Riley.”

![]()

That's it until next time!

A good step-up from the first in the series

| I read The Sun Shard - the first in this series - back in November, and purchased the second volume as soon as I spotted it for sale. The Dead Gods is a self-contained work, and enough of the back story is given that it makes sense on its own, but clearly it will appeal more to those who have read #1. The Sun Shard introduced us to one facet of the world, focusing on the conflict around a particular region. The Dead Gods now expands our horizons to the wider context. We learn more - a lot more - about the major national players who had fuelled that battle, and the particular agendas which drive them. We also find out about some of the lesser factions, and their hope to leverage the confusion of war to their own benefit. The book tells its story through multiple different perspectives, but manages not to get lost in confusion as it does so. This device reinforces the sense of a patchwork world, divided by cataclysm where it could potentially be united. In the first book, the focus was predominantly on physical weapons, and the skill and dexterity with which they are wielded. Magical tools were present as a background element in the fight - nice if you could get them, but not a disaster if you couldn't. Now, they have become essential. The two ways of waging war need each other's support. The basis for supernatural power is being slowly revealed in hints and clues, and there is an inescapable conclusion that it is all highly dubious, whether wielded by what we think of as the bad guys or the good. I was particularly pleased that we learn more about the Flint Folk and their culture. Like everybody, they have internal divisions and feuds, but they have definitely emerged as the most likeable of the factions. They represent the persistence of something which has been lost in our world - a hominid species close enough to us for easy communication, but different enough to provide perspective and challenge. This volume has successfully addressed the technical proof-reading problems which affected the first. Also, women are given a more central position in the flow of events. The various cultures cannot be described as equal-opportunity, and a woman's chief access to power is still through her sexuality. However, female voices and influence are starting to be heard at the higher levels of society. The story is clearly in full stride now, with the various key figures moving into place towards a showdown. The Dead Gods is a worthy successor to The Sun Shard, and I will certainly be looking out for the third part as and when it appears - hopefully next year. |

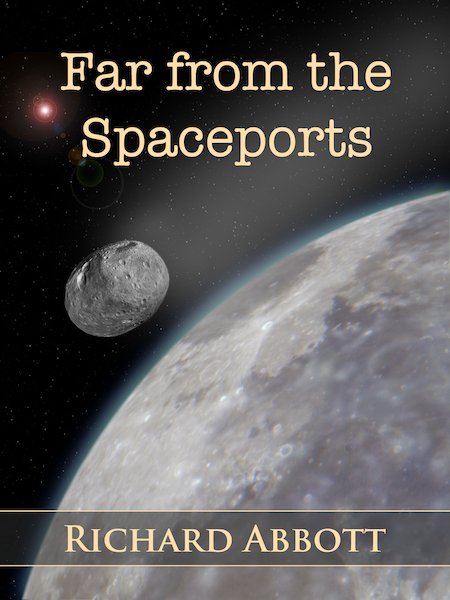

Far from the Spaceports - Quick wits and loyalty confront high-tech crime in space

Far from the Spaceports, a new science fiction book set in the fairly near future, explores the relationship between human and artificial intelligence, solving high-tech financial crime in space.

Read a sample online at http://issuu.com/mattehpublications/docs/far_from_the_spaceports_sample

Download a free Kindle or epub sample at http://www.kephrath.com/FarFromTheSpaceports.aspx

Buy the book at http://www.amazon.com/Far-Spaceports-Richard-Abbott-ebook/dp/B017WODIUU/ and other global Amazon stores

Quick wits and loyalty confront high-tech crime in space

Welcome to the Scilly Isles, a handful of asteroids bunched together in space, well beyond the orbit of Mars. This remote and isolated habitat is home to a diverse group of human settlers, and a whole flock of parakeets. But earth-based financial regulator ECRB suspects that it’s also home to serious large scale fraud, and the reputation of the islands comes under threat.

Enter Mitnash Thakur and his virtual partner Slate, sent out from Earth to investigate. Their ECRB colleagues are several weeks away at their ship’s best speed, and even message signals take an hour for the round trip. Slate and Mitnash are on their own, until they can work out who on Scilly to trust. How will they cope when the threat gets

personal?

A tale of betrayal, forgiveness, and passion

The Long Shadow, by Loretta Proctor, is the forerunner to Dying Phoenix. I read them in reverse order, but this didn't affect my enjoyment of either book. They can be read quite separately. The Long Shadow spans a considerable period of time, from the middle of the First World War until the late 1940s. It largely describes the lives of a mother and son, Dorothy and Andrew, caught between lives in England and Greece. The very different environments - of land, culture, community, and family - are excellently captured by Loretta's writing.

For all the social changes in Britain brought about by two world wars, a countryside house in the Cotswolds serves as an emblem - it is a haven of peace and sanctuary. It provides some glimpse of pastoral peace. The Greek landscapes, on the other hand, from urban Athens and Thessaloniki through to the remote rural villages of Macedonia, are in constant flux, repeatedly scarred by external invasion and internal feud. The picture of northern Greece at the end of the book is quite different from that at the start, after it has been touched by war, fire, land clearance, rivalry, and modernisation. It is a harsh time and place to live, but occasionally, and unexpectedly, it provides vistas of grandeur and beauty. It sways between hostility and brotherhood - but always with a profound and unpredictable passion.

The Long Shadow also captures, in bold manner, the highs and lows of having mixed-culture ancestry. Andrew can never decide whether he is British or Greek in his soul, and for much of the book he oscillates between them as he tries to find his own identity. His betrayal, in turn, of each of his parents has a terrible symmetry and inevitability. But it also has an entirely fitting asymmetry, matching the cultural background of each parent. The book pursues multiple overlapping arcs of betrayal and reconciliation, estrangement and forgiveness - some of these arcs can be closed, and others remain forever open and unresolved. Truly, living with a cross-cultural heritage can be fraught with difficulty and confusion.

Occasionally I come across people who say they can judge a book after reading only the first few pages. In the case of this book they would have missed a rare treat, since the book builds steadily from a gradual start towards a series of emotional and relational high points. It's long - nearly 500 pages in paperback - but well worth it.

In summary, I really enjoyed The Long Shadow, and recommend it to others.

A first glimpse into an innovative and unusual world

Sun Shard, by Rob Bayliss, is a fantasy novel set in a world with a level of technology roughly like that of the English Civil War. There are hand to hand edged weapons, alongside moderately reliable muskets. But there are also giant beasts reminiscent of those which our Stone Age ancestors had to confront. There is also a magical component, important to the storyline but practiced only by a handful of people. The links between magic, religion and spirituality are teasingly opened up as the book proceeds, but remain ambiguous for later books to develop.

Sun Shard is only part one in the series, but happily it is self contained as a book, and achieves closure on the central crisis raised. In its course, we are introduced to the major people-groups, beginning with a rather feudal rural group and moving progressively onto larger and more urbanised scales.

We mainly follow the actions of one of these rural individuals. He starts the book as a skilled but unimportant scout, and through both force of circumstance and personal choice becomes increasingly crucial to events. In the process, he comes to reevaluate the nature of the conflict he is caught up in, and begins to appreciate the real enemies. I am sure that this process will continue in subsequent books.

The world is very male dominated. There is only one female character who is important to the plot, and other women are either idealised, or reduced to sex objects for the soldiers and leaders. It's a difficult world to live in for both men and women, unless a person can find the right niche and the right group of companions.

The plot drives along in a brisk way. There are battles on land and sea, in which intelligent use of technology and resources is as important as pure force. But alongside that, the slowly opening insights into the deeper moral struggle provide a parallel plot alongside the fighting which adds considerably to the interest of the book. There are a number of points where parallel actions are going on in different locations, but any possible confusion is avoided by clear exposition.

On a technical level there are some typos which distract from the reading, especially around the use of apostrophes. Also, some of the longer sentences could do with more use of commas to help navigate through them. All of these could be caught with another editing sweep through the text, and some people will not mind the slips as they race through the pages.

In short, an interesting and involving world, with a coherent inner logic and increasing insights into a deeper moral and spiritual plane. The book ends with a short teaser for the next book in the series.

Life was tough in ancient Rome...

Spartacus, by Robert Southworth, is built on a what-if premise - what if Spartacus was not killed at the end of the slaves' rebellion in 73-71 BC? What if instead he was captured, and turned by one of the Roman factions into an agent to carry out hazardous missions - a sort of Jason Bourne of the Roman world? As a premise it makes sense, as he was highly skilled as a fighter both by natural talent and on-the-job training. Too good to waste by execution, really, so long as there was a reliable way to keep him under control.

That accomplished, Spartacus comes under the direct leadership of a man he learns to respect, and gathers around him a diverse band of other fighters. The scene is set for a challenging tour of operations involving hazardous journeys by land and sea, trickery and betrayal, and a final showdown as the climax of the book.

A multi-layered vision is painted of Roman society. The life a man can build for himself is defined partly by innate or learned skills, but overwhelmingly by the power of the patronage he can find. We are introduced to hierarchies of power in the Roman world, most of which are ruthless in the pursuit of their own interests and brutal towards their enemies. The picture is effective, and it didn't take long for me to decide that I would not have enjoyed living in that culture - and most likely would not have had a very long life within it.

Difficult for men, then, and many times more so for women. For them, powerful protection in the form of husband or master was a necessity, and there was basically no legal recourse against brutality. In Robert's book, women provide a background element of stability and passionate release, a desirable goal to yearn for when the fighting is done. For the good guys, this means a faithful wife: for the bad guys, a collection of dispensable slave girls. But there are no central female characters in this book, and it is difficult to see how there could be in this vision of Rome.

The book is very fast paced, as we rush with Spartacus and his gang from threat to threat, and combat to combat. Occasionally we get glimpses of other aspects of Roman life, but all too quickly the men are pulled away to the next fight, learning how to work together as a team as they go.

On a technical level the book could have benefited from another editing session or two. More commas would have helped read through the longer sentences, and changes of viewpoint from one character to another could have been signalled more smoothly in the text. There was nothing of this nature that could not be solved with a minor correction of the text.

Spartacus succeeds as a visceral, fight-focused journey into small team combat in ancient Rome. It also supplies the lurking sense that there are much bigger games afoot, and that at some stage the central characters will be caught up in them. There are follow-on books, which one suspects will increase the stakes, but Spartacus is complete as a novel in itself.

A window into modern Greek history

Dying Phoenix, by Loretta Proctor, opened a window for me on a slice of modern history I knew almost nothing about - Greece, in the months surrounding the generals' coup of 1967. In recent months, Greece has once again been forefront in international news, and although the main issues today are economic rather than political, I came to understand something of the passion that fuels debate there.

There's a lot of background that needs to be conveyed to the reader, and this is done largely through dialogue. Many different points of view are portrayed here. Indeed, there is a whole spectrum from those who supported the right wing army position, right through to those who were implacably hostile to it. Although the opinions of the central characters are clear, the author presents the diverse range of opinions credibly and sympathetically.

I discovered before long that Dying Phoenix follows on from a previous book, The Long Shadow. Broadly speaking, this second story follows the fortunes of the generation living in the legacy of the first. I am sure that familiarity with that earlier book would give extra depth to some of the characters, especially the older ones. However, the two works are self-contained, and this one can be thoroughly enjoyed in its own right.

Dying Phoenix - appropriately enough given the mythological reference - holds out the possibility of future hope against the background of disappointment in the present. Indeed, a main theme of the book is how people face failure, both their own and that of others. Idealism is a powerful force, particularly amongst the young, and seeing one's ideals being crushed remorselessly by superior strength is a terrible thing. In among the violence and intolerance, however, there are signs of rebirth, as the fires of destruction exhaust themselves. Also, those with longer memories can see that this struggle is only the latest in a very long series of similar ones. There is a continual hope that this time it might be consummation rather than recapitulation - a worthy dream, but one that is not yet fulfilled.

Geography plays a key role in the story, ranging from English locations such as Brompton Cemetery and Kensington in London, via urban Greek settings in Athens and Thessaloniki, through to rural havens in the Macedonian mountains. Each place has its own character, and its own inhabitants, who blend self-interest and self-sacrifice in different measures.

Dying Phoenix presents these key events in the life of modern Greece through the eyes of quite ordinary people. You will not find here a historical analysis of the generals' actions or motives, but rather the personal perspectives of those caught up in the turbulence. Some are eager for direct involvement, while others are anxious to avoid it, fearful of the consequences for their family. It all makes you wonder how you would react if you had been there.

In short, I found this a fascinating account of a turbulent time for many individual Greeks as well as for Greece as a nation. The difficulties and pains of those days are not avoided, and this struggle brings the characters to life. If you like to immerse yourself in the details of a situation, as seen through the eyes of ordinary people, Dying Phoenix may well be for you.

The natural beauty of the Wild West comes to life

Written as one of “The Review Group” Review Volunteers, see http://thereview2014.blogspot.co.uk

It is a very long time since I read a Western. Back in school we had Shane as a class book, and from the same era (and I'm showing my age here) I was a keen watcher of the two television series The Virginian and The High Chaparral. But since those long-ago days I think I have only encountered the Western genre in films. To this British reader, coming across placenames like Rio Verde or Yuma evokes a feeling of going into a fantasy land, where anything might happen.

So it was with an entirely appropriate sense of riding into the unknown that I started this book. There were familiar elements that you meet almost at once. There is the mysterious man with the shady past, the abandoned wife struggling to make ends meet for her family, the lawman balancing his sense of natural justice with the pedantic legalism of "wanted" posters, Indians of several kinds, the optimistic prospectors hoping to strike lucky, and a whole mixture of diverse individuals making up the rest of the small town. There are motives of hate, love, revenge, self-sacrifice, over-protectiveness and partnership. The human environment was intricate and intriguing.

What I had not expected was so much enticing description of the natural world. The untamed beauty of the region comes over vividly in the writing, and successfully imparted a delight in these days of wildness.

==========

Mounds of brittlebush dotted the incline. Dried stems once held flowers, but now burned naked, stabbed through clusters of gray-green leaves. Waxy creosote glistened in the harsh light as the sun climbed across the sky's bleached dome.

==========

or...

==========

When the clouds parted the desert's drab browns and greens had been replaced with splashes of red, vermillion, ochre, olive, yellow. Flat land, soaring monoliths, all a rainbow of colors. Directly below him the ground opened in a deep gash. A clear turquoise stream ran through it and a spindly rock formation towered almost to the top of the surrounding cliffs.

==========

Thinking back, I should have expected this, as the old TV shows were full of spectacular sunsets and desert vistas alongside the human interactions. Apparently my adult appreciation noticed much more than my childish eyes had ever done. Here, the stern vividness of the land throws into stark perspective the actions of the men and women who live in it. Several of the characters have family ties back in the softer, safer states on the Eastern Seaboard, and could easily return there. However, surrounded by a natural world like this, one can entirely understand why they do not go back.

There are, of course, differences in this plot from the ones I remember from childhood. The Native American groups are presented in a much more diverse and compelling way than used to be the case. In particular, their connections with the land - for both good and ill - are an important feature of the novel. The world of the dead, of dreams, and of spirits is both accessible and elusively remote. People's motivations are more complex and more real. Happy endings are elusive.

On a technical level, the book is well presented and prepared. For my taste I would have preferred a few more commas here and there to help readability, but this is a minor issue. The heart of the book is not its technical presentation, but the way in which the human story draws you into the vastness of the western landscapes. You emerge from this book with a sense that the world is very large, and that with a little perseverance, a person might find all manner of beauty in it.

Britannia’s Shark is the third published naval fiction book by Antoine, following the exploits of the 19th century Royal Navy captain Nicholas Dawlish. The books can each be read separately and there is adequate contextual material to fill in any gaps the reader might have.

Dawlish’s career is characterised by a series of secretive operations to further British interests, well outside the publicly visible face of the Navy. He is one of the servicemen of that age who were willing to experiment with a wide range of emerging technologies, which together were rapidly transforming sea travel and sea warfare from the sailing ships of Nelson’s time to the ironclads of the First World War. Indeed, other than ship-based aircraft, all of the ingredients of modern naval warfare were well formed during Dawlish’s lifetime.

The main emerging technology of this story is the submarine. Antoine vividly captures the claustrophobic horror induced in a man who has been used to open horizons and fresh air, when faced with the constricting darkness, clutter, and polluted atmosphere encountered in this very early prototype. Only total commitment to his calling, and complete acceptance of the necessity of his actions, could overcome Dawlish’s visceral rejection of his situation. The mixed reception of the submarine as a weapon is clear – recognition of its military value alongside repugnance at connotations of cowardice and deceit.

I enjoyed this story considerably more than its predecessor. For one thing there was a much richer, and (for me at least) a much more interesting blend of politics and cultural dynamics alongside the ship and land based fighting. For another, Dawlish’s wife Florence reappears in a crucial role throughout this book, whereas she was relegated to a very minor scene in Britannia’s Reach. Florence is a fine character, and a splendid companion for Nicholas, so it was very pleasing to see her courageously facing danger alongside him.

The political backdrop is also fascinating, as Dawlish is forced to deal with several different factions, all competing for influence and technological advantage. British, Irish, American and Caribbean interests intersect in the story, providing a shifting ground of ambitions and frailties on both national and personal scales. Often in the story – as so often must happen in real service life – respect and friendship cut across the lines drawn by governments.

On a technical level, the book has not been quite so thoroughly edited and proofread as previous volumes, but the typographic slips are still few and far between.

In short, a fine addition to the life story of Nicholas Dawlish, and the extra human and political dimensions explored here push this one up to 5* for me. I shall be looking forward to the next in the series as and when it appears.

History and myth in the Late Bronze Age brought convincingly to life

I thoroughly enjoyed Hand of Fire from start to end. Judith has tackled a difficult combination here, blending soundly researched historical fiction with mythic elements. In this she is placing herself solidly in the tradition of the Iliad, from which the basic setting of Achilles and Briseis comes. In the process Judith also pleasingly avoids the common approach of demythologising ancient material. The ambiguities and difficulties of a story integrating both humans and gods are welcomed rather than shirked.

One of the central questions here that stood out to me was whether it is possible to love someone who is more archetype than person. In one sense such a love is larger than life and sweeps everything else aside: in another it is completely impossible, and doomed to disappointment on both sides. That, for better or for worse, is where Briseis finds herself in relation to Achilles.

Religion and spirituality are key themes in the book. Briseis' world view, its habits of thought, and the rituals that attend it, are foundational to the story, and are well constructed and appropriate to her Bronze Age context. I thoroughly enjoyed the blend of faith, doubt, superstition and logic that she displays, which will be recognisable to modern readers just as much as to her contemporaries. Achilles is a step beyond such constraints, operating in a dimension of certainty most of us cannot. His passions are larger than ours, incomprehensibly so at times, and like a spiritual amphibian he moves comfortably in the liminal space between this world and the next, between the terra firma of his father, and his mother's measureless ocean.

As you can tell, Hand of Fire made a great impression on me, and I would recommend it to anyone who wants to explore the tail end of the Bronze Age. Read it either as soundly researched history or as an exploration of archetypes: either way it is compelling.

Short and sweet: an invitation to read more

Candle's Christmas Chair was available as a free download, to which I was drawn as a result of a Christmas blog hop. I was slightly dubious at first, since "historical romance" is not really my normal fodder, and the last book I read which had been billed as such had been very disappointing. However, I was encouraged by the extract I had read, so persevered, and was glad that I did.

Jude has been careful in her limited use of the Napoleonic War setting, and in particular the difficulty of the general population at hearing news of engagements. Part way through the story a crowd assembles to hear a description of the battle of Trafalgar being read out: news was a shared experience, not a personal one.

The main focus, however, is the intersection of individuals rather than the fate of nations. Jude spends most of her narrative time describing the way two individuals come together despite differences in social position, prior misunderstandings, and the mixed responses of those around. Along the way we are treated to snippets of insight into the period and its customs.

The book is relatively short - novella rather than novel, and the outcome is never seriously in doubt. In that span there is not a lot of opportunity for elaboration. However, Jude has deliberately pitched Candles Christmas Chair as an introduction to her longer works, and as such it works extremely well.